- The Tea Plant: Camellia sinensis

- History and Culture

- Health Benefits

- Origins

- Processing Methods

- Harvest

- Six Types of Tea

- Processing Chart

- Caffeine

- Botanical Blends

- Steeping

- Cupping

-

The Tea Plant: Camellia sinensis

All true tea comes from Camellia sinensis, an evergreen shrub that is native to southwestern China’s Yunnan province. Three original varieties of Camellia sinensis are recognized. They are var. assamica, var. chinensis (or sinensis) and var. cambodiensis. The assamica plant is native to northeastern India’s Brahmaputra River valley region, Assam, and is known for its broad leaves, ability to thrive in hot, humid, low-lying environments and for making a robust cup full of body and color. Assamica is generally, but certainly not always, planted in black tea producing regions like Assam, East Africa and Sri Lanka.

Var. Assamica on the top; Var. Chinensis on the bottomThe chinensis variety is known to be the original tea plant indigenous to China and is known for having a smaller leaf, a multi-stalked trunk and for making an aromatic, flavorful cup. Chinensis has small leaves and a hearty constitution so is planted at high elevations and in areas with difficult climates. For example, China, Japan and Turkey.

Var. cambodiensis is used in tea research stations around the world in the development of new tea cultivars and for scientific purposes. It is not grown or processed for consumption.

-

History and Culture

Asia: According to legend, tea was discovered by the great herbalist and Emperor Shen Nung in ancient China in 2737 BC. Legend tells that while he was meditating under a tea tree, the wind blew and a leaf fell into his cup. He was so impressed with the meditative and restorative properties of the ensuing brew that he popularized the consumption of tea amongst his people. For thousands of years, tea consumption was relegated to China before spreading, largely by Buddhist monks, to other parts of Asia, primarily Japan in the 1100s.

Europe: Tea made its way to Europe in the early to mid 1600ds. There, it was enjoyed by the upper class that developed a taste for black tea. In an effort to break China’s monopoly on the tea trade, the British began planting it in their colony, India, in the 1800ds.

Americas: Tea made its way to the Americas with colonization but became an out- of- fashion symbol of British rule and taxation without representation around the time of the American Revolution, when the colonists famously threw tea overboard in protest during the Boston Tea Party. Today in North America, tea is having a renaissance. Americans are looking to tea for its health benefits, flavors and for the conscious, positive, healthy lifestyle it helps achieve. We are trading our low quality tea bags for higher quality loose-leaf teas, full leaf tea sachets and low sugar ready to drink teas. With Oprah, Deepak and Starbucks all now coming over to tea, all signs point to tea’s continual growth in years to come.

Firepot Nomadic Teas is committed to supporting this growth with education. To that end, we focus on teaching skills and inspiring understanding.

-

Health Benefits

Since Shen Nung’s time, tea has been revered for its mental and physical health benefits. Mentally, it has been used for meditation and focus for millennia. This is in part due to L Theanine, an amino acid found largely in green tea, that increases the alpha waves in the human brain and induces a relaxed, focused state without drowsiness¹. Physically, it is the antioxidants, specifically the catechins (ECG, EGC and ECGC) that fight the free- radicals that cause cancers, that are to thank. Tea has also been credited with improving cardiovascular health, fighting Parkinson’s disease and aiding weight loss, to name a few. In short, it is part of a healthy lifestyle.

-

Origins

Camellia sinensis thrives in warm, humid climates with regular rainfall and well-drained, acidic soils. Being an adaptable plant, it is cultivated in over 40 countries around the world today.

Classic: Aside from China and Japan, classic tea origins include Taiwan (which used to be called Formosa; hence “Formosa Oolong”) and areas where tea was originally cultivated by the British Empire: India and Sri Lanka (then known as Ceylon; hence “Ceylon tea”). You will find black teas growing predominantly in these areas because of the British affinity for black tea.

New: New origins are being developed all the time. Of local importance are both the burgeoning Hawaiian and northwestern United States tea terroirs. Other important origins to specialty tea are Nepal, which began growing in earnest in the 1990s and is now producing world- class teas; East Africa, which developed a tea industry in the 1920’s and is now the largest exporter globally of black tea; and other Asian regions such as Vietnam, Bhutan, Korea and Australasia. -

Processing Methods

Tea can be produced in one of two methods: Orthodox or CTC (“Crush Tear Curl”).

Orthodox: The Orthodox method of tea processing requires the tea to be processed by hand or by machines that mimic hand rolling. This ensures that only quality leaves and buds are picked and that they stay whole. Most of the tea for the specialty tea industry is made using the Orthodox method, as it preserves the aromatic oils in the leaf that make a full-flavored cup.

CTC: The Crush, Tear, Curl method was developed primarily for the black tea industry to process tea more quickly and prioritizes color and strength of a tea, rather than aroma, flavor and visual appeal. This method utilizes machines to crush and tear the leaves, resulting in tea that resembles small pellets. Because of the smaller size leaves they oxidize much faster, saving even more time. These leaves are primarily used in tea bags, iced teas and blends and are known for their fast infusion time and ability to deliver a very bold cup. While CTC teas are not generally considered “specialty”, there are some very decent ones as well as Fair Trade and Organic ones on the market and they serve a specific niche in the overall tea market. -

Harvest

Plucking: Most quality teas are picked by hand. There are many types of plucking styles used by garden managers; each tea calls for a specific pluck. Also, plucking is an essential part of tea plant maintenance. A common term in the Specialty Tea Industry is “Two Leaves and a Bud”, which refers to the “Fine Pluck”—the most common pluck for specialty teas. The “Imperial Pluck” refers the terminal bud of the plant and the leaf just below it. In the Chinese terminology, Mao Feng is the Fine Pluck and Mao Jian is the Imperial Pluck.

Flushes: A flush is a harvest in tea terms. The first flush of the spring is known for its extreme aromatics due to high levels of essential oils stored over winter in these first, tender leaves of the year. In many cases, first flush is the most sought-after flush of the year. Subsequent flushes are known for other particular characteristics like unique flavor or yield, depending on origin and climate.

Depending on the origin and its climate, there are generally between 3 and 6 flushes a year.

-

Six Types of Tea

The six types of teas (black, oolong, green, pu-erh, yellow and white) are distinguished by processing methods and levels of oxidation.

Black: The most commonly drunk tea in the West is black tea. Black tea is completely oxidized tea, thus offering a cup with more developed tannins, strength and body.

Black teas include our Italian Grey, Firepot Breakfast and Firepot Chai.

Oolong: Oolong tea is semi-oxidized. Its manufacture is an art form, resulting in flavor notes ranging from fruity, sweet and floral to mineral, roasted and earthy. Fujian Province, China is the birthplace of Oolong tea and today most quality oolongs are made in Taiwan and China. Firepot’s house oolong is a Tie Kwan Yin (“Iron Goddess of Mercy”) Oolong from Anxi, Fujian, China.

Green: Green tea is not oxidized. After being harvested, the leaves are immediately steamed or pan fired to stop the oxidation process. This allows the tealeaves to keep their distinct green color, high levels of antioxidants and delicate vegetal and floral notes. Green tea is processed predominantly in Japan and China with the Japanese tea makers steaming the leaf and the Chinese makers roasting it. Firepot’s Japanese Peasant Tea (“Genmaicha”), Moroccan Jasmine Mint and Himalayan Mountain Green Tea are examples of green teas.

White: White tea is the least processed of all the tea types. In the processing of white tea, the terminal bud of the plant is plucked and dried. White teas have very delicate flavors and are less astringent than other tea types. White teas are authentic only in Fujian, China but produced around the world.

Pu-erh [Poo-err]: This tea is grown exclusively in and around the county of Pu-erh in Yunnan China. It is made from a green tea called “mao cha”. It is steamed, fermented and then aged anywhere between a few months to several decades, depending on the type of Pu-erh being made. Pu-erh tea is considered to be a living food with probiotics and digestive benefits like sauerkraut and yogurt. “Sheng” or “raw” Pu-erh is made using the traditional process: fermenting naturally over time. “Shou” or cooked Pu-erh is a modern way of processing Pu-erh more quickly by artificially fermenting the tea. Highly prized Pu-erhs have been aged for over 200 years!

These teas are known for their earthy and woodsy aromas, robust smooth flavors and health benefits. They have developed a cult-like following in recent years.

Yellow: Yellow tea is a very rare tea type made in China and Korea. It is processed very similarly to green tea, but undergoes a post processing fermentation, or slow drying. This changes the taste of the tea, making it more mellow and smooth and accentuating notes of dried fruit and moss.

-

Processing Chart

-

Caffeine

Amount by tea type: Recent research disproves two outdated theories regarding caffeine and tea: 1) Most of the caffeine is extracted during the first 10 seconds of steeping 2) The less processed a tea is, the lower its caffeine content. It used to be believed that the order of caffeine content in tea, from lowest to highest, was: white, green, oolong, black. Now we know that the amount of caffeine in your cup is dependent upon varietal, terroir, manufacture and steeping. For example, a Long Jing Shi Feng, a famous Chinese green tea, was recently found to contain over twice as much caffeine as a robust, black Assam breakfast tea. It also was found to release caffeine even after steeping for 10 minutes.

Caffeine in Coffee vs. Tea: When compared to coffee, tea is known to give a more alert feeling over a longer period of time. This is because the catechins (polyphenols) in tea bind to caffeine and slow its release. The caffeine in coffee is released into the bloodstream in 2-5 minutes and dissipates within 2-5 hours. The caffeine in tea is released slowly for 10 hours in the body.

The tealeaf actually has more caffeine, gram to gram, than the coffee bean. In most instances, though, coffee is brewed using more product, by weight, than tea. For example, you would use about 10 grams of ground coffee beans to make a 6 ounce cup, while you would use only about 5 or 6 grams of tea for an 8 ounce cup, depending on the tea.

-

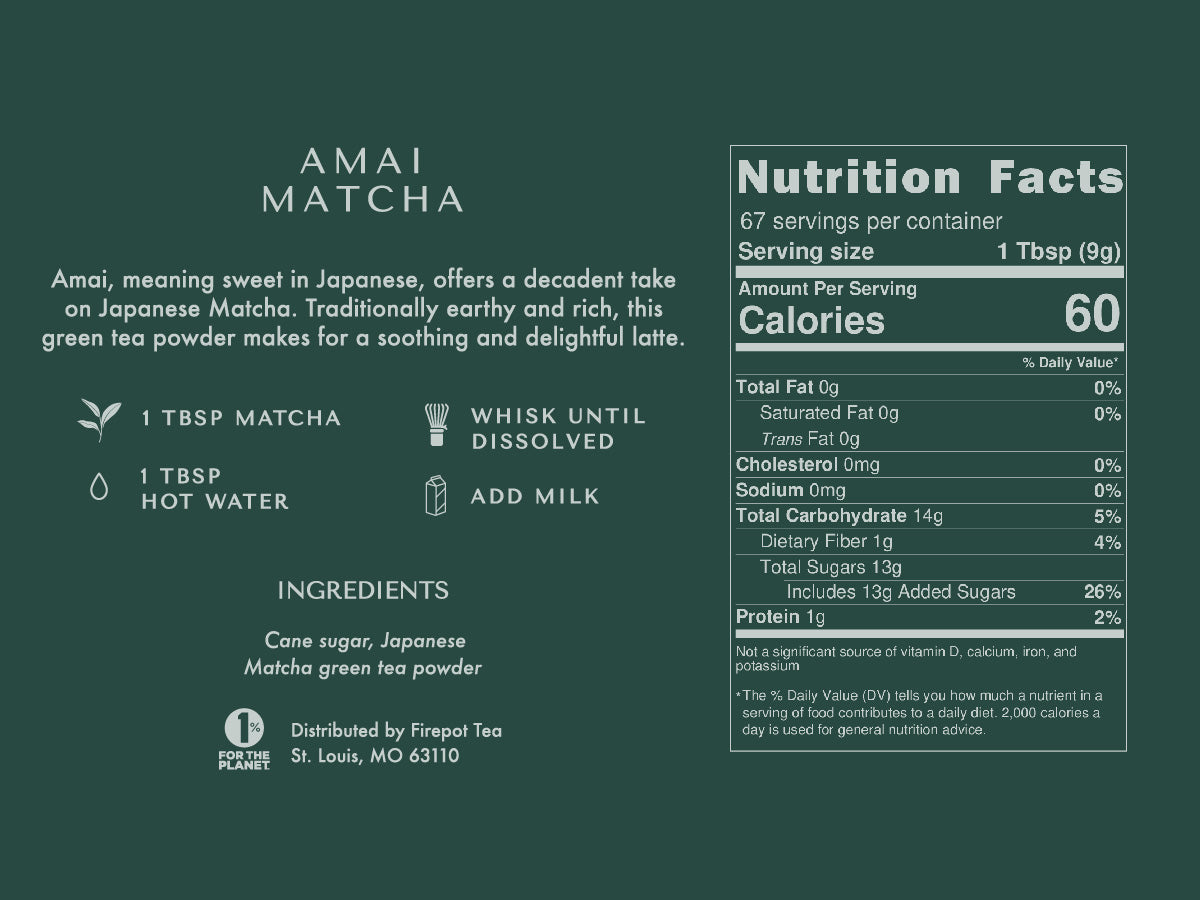

Botanical Blends

Botanicals such as chamomile, peppermint, hibiscus and rooibos are not technically called teas because they are not derived from Camellia sinensis. They are more accurately called tisanes (from the French word “herbal infusion”) or botanical blends.

Tisanes are caffeine free. They are usually fruits, dried flowers, roots, herbs, plants or a combination of these infused with boiling water.

Other botanicals, like Yerba Mate and cacao, contain some caffeine.

Firepot’s Hibiscus Elixir and Indian Rose Garden are examples of caffeine-free botanical infusions.

Wellness Teas: Wellness teas (those consumed primarily for their health benefits) are a fast growing segment of the tea industry, as people are increasingly drawn to functional foods. There are wellness teas on the market today that claim to cure a sore throat or an upset stomach, to make you beautiful, limber or smart and to increase longevity. It is important to note that the FDA is taking a hard line with tea companies making health claims and it is no longer possible to legally do so with out copious scientific research to back up claims.

-

Steeping

It is important to remember that at the end of the day, tea is just water and leaf and taste is highly subjective. However, as tea experts, we set specific parameters for steeping our teas so that they can be enjoyed to their highest potential.

These parameters are:

1. Temperature: Very high temperatures extract more tannins, create a more astringent cup and can burn off both amino acids and volatile, fresh aromas. If astringency, strength and body are desired, a very hot or boiling temperature may be ideal. Very aromatic green teas will show best when steeped below 160°. For example, our Japanese Peasant Tea.

Most of our teas are steeped with water that is between 160° and boiling (212°). We aim to balance astringency, body, strength, and aromatics.

2. Time: Flavor, caffeine and other chemical compounds are released into water at different rates between 1 second and 20 minutes. By understanding how a tea is supposed to taste, we set an infusion time that is ideal for that tea.

3. Weight: The industry is moving towards using more leaf (coupled with shorter steeping times) for a more concentrated flavor notes. Most of our teas are steeped using just under 1 gram per ounce.

Other influences on the quality of the cup are:

1. Water quality: Water quality is critical, so we recommend using filtered or spring water. One can study the exact effect of a water’s pH and mineral content on tea to craft the most perfect cup, but for our purposes, we start with filtered or spring water. It is fun to taste your favorite tea in different environments with different waters; you will discover just how different the same tea can taste!

2. Teabags VS Loose Leaf Tea: Teabags offer convenience, but they sacrifice quality. They constrain the leaves to a small space where they cannot fully expand and release all of their flavors. This can be ok for CTC and very small particle size teas, but in the case of full leaf, high quality teas; the leaves should be free to “swim around” in the water for an even and full-flavored infusion.

-

Cupping

To evaluate and compare teas, professional tea tasting is employed. Following the exact same protocol each time will ensure consistent cupping and dependable observations.

Follow the steps below:

1. Line up as many cupping sets across a tasting table as there are teas to taste.

2. Place each packet or sample of tea just above each cupping set on the table

3. Fill each cup with 2.5 grams of tea and pour out the remainder of the tea from the packet into a tray in front of each cupping set.

4. Fill each cup, one at a time, with boiling water.

Boiling water is used to draw out all flavors in the tea, good and bad, for accurate tasting.5. Steep for 5 minutes.

6. Decant each tea, one at a time in the order that they were poured, taking as long to decant as you did to pour, into tasting bowls, being sure to tilt the cup slightly downwards so that all the liquid drains out.

7. Firmly shake the cup upside down so that the leaves fall into the inside of the lid. Then you can place the lid, leaves up, on top of the cup to smell the aroma of the steeped leaves.

8. Wait at least 5 minutes to taste, as flavors are easier to detect in tea that is around 180° or below. Once teas reach around 100°, the flavor notes begin to dissipate.

9. When cupping a tea, evaluate the appearance of both the wet and dry leaf, the bouquet of both the dry and wet leaf, the color and clarity of the liquid, flavors, aromas, the feel of the tea on the mouth.

Teas can also be brewed with their specific cupping parameters (rather than 2.5 grams/ boiling water/ 5 minutes) in tasting cups for consumption or education.